In this article we cover:

- What is a suspended floor?

- Suspended floors using structural concrete, from reinforced precast to ribbed

- Suspended ground floors using structural timber

- Airtightness considerations

- What are timber floor joists and how to use them

- Notches and holes in joists: watcpoints

- What are open web joists and I-joists: where and how to use them

- What are attic roof trusses and how to use them

- Engineered timber options: from glulam to LVL

- How to check for timber quality and strength

A suspended floor is one that’s built across walls, beams, columns or foundations, spanning across an open space or void underneath. Upper storey, intermediate floors and mezzanine floors are all suspended.

The most common types of suspended floors that we use in domestic construction today are based on either reinforced concrete, or on a timber based joist construction method.

Incidentally, a reinforced concrete floor which is cast on site onto an underfill base is somewhat of a hybrid between a ground supported and a suspended type of construction. This is because it will be designed to act as a suspended floor when fully cured but relies on the underfill to support it initially, until it gains sufficient strength to support itself and any other design loads that may be imposed upon it.

It should be noted that the ground level of any voids below suspended ground floors must be sealed to prevent infestation. This is usually achieved with 50-75mm of concrete on a layer of underfill.

Suspended floors using structural concrete

Of the examples given below, in modern domestic construction the first two or three are the most often used, but the others present unique solutions which should not be ignored when considering floor design.

You can also obtain precast concrete floor units with inbuilt insulation, which neatly solves the tricky problem of how to fix insulation under precast slabs at the ground floor level. It is possible to directly plaster the underside of most precast concrete slabs to form ceilings, but the necessity of incorporating cables, ducts and recessed lighting, etc. means that most will require a ceiling to be suspended about 150 mm below the slab.

- Simply reinforced precast concrete slabs or planks are usually 600mm wide by 150mm thick and will span up to about five metres depending on the manufacturer’s specification.

- Prestressed reinforced hollowcore concrete slabs will cover greater spans than the simply reinforced types and can range in thickness from 85mm to 500mm.

- Beam and block floors use prestressed reinforced concrete beams as the structural elements of the floor, where the beams are set as inverted Ts and ordinary concrete blocks are set between them.

- Composite floors are used to create large open plan spaces, so are usually found in commercial or industrial buildings but can be used in larger domestic building projects as well. They are usually built using reinforced concrete which is cast on site on top of steel decking sheets which are fixed onto a framework of steel beams and columns.

- Ribbed floors use shallow concrete beams or ribs and can be built as troughed floors which are ribbed in one direction, or as waffle or coffered floors which are ribbed in two directions. Compared weight-for-weight with flat slab floors, ribbed floors can generally span further and carry more of a load.

- Vaulted floors are found in older buildings where the underside of the floor is constructed in arched shapes using stone or brick, with later examples in concrete. A modern take on the idea has recently been developed by researchers at the Universities of Bath, Cambridge and Dundee. Their system uses 75 per cent less concrete than a flat concrete slab covering the same floor

area. The ACORN Project team manufactured their prototype floor in a number of curved and

jointed precast concrete pieces that can be disassembled and reused. The carbon reduction

was calculated at 60 per cent and it is believed that this figure will improve as the process is further refined. - A hollow pot floor is another version of the ribbed floor and is cast on site using hollow clay

or concrete pots as permanent formwork.

Suspended ground floors using structural timber

Firstly, it is quite unusual nowadays to see a suspended timber floor constructed at ground floor level. This is largely due to the labour intensive process required to incorporate a radon barrier and a sufficient thickness of insulation, all whilst controlling thermal bridging, damp proofing, air permeability and interstitial condensation risk.

Having said that, if it’s what you really want, don’t let the complexity put you off. It can be done but requires a proper design and faultless workmanship. Building this type of floor requires support from brick or blockwork dwarf or sleeper walls to carry it at the correct level above the ground underneath.

Airtightness

Nowadays, in order to maintain high levels of airtightness, bare timber (e.g. joists) should not be carried in the traditional way through the internal skin of blockwork or brickwork cavity walls. This practice means that, as all joists will continue to shrink until they reach a stable moisture content, air leakage pathways from and to the wall cavity will open up around the ends of the joists, even though they might have been sealed with mortar after placement.

Flexible sealants should not be used to try to counteract this. One solution is to place preformed rigid plastic pockets into the joist holes in the walls and properly seal around them. The joists then fit into the pockets and any timber shrinkages will not cause air leaks. Another solution is to not create any holes in the walls at all, but to support the joist ends on galvanised steel joist hangers which are directly fixed to the inner faces of the walls. All of these methods require special attention to be paid to

the provision of lateral support to the walls.

Timber floor joists

For upper storey floors then, the traditional timber floor uses solid natural timber floor joists which should be spaced at such centres as to make the most economical use of the maximum spacing required by both the floorboards or timber decking above and the plasterboard for ceilings underneath.

The span of the joists will depend on the floor loading and on the grade of timber used. A higher strength grade number equates to a stronger but usually more expensive timber. However, the stronger grade should require a smaller timber cross-section for a given span and joist spacing, so it may work out to be more economical.

To find the most economical solution, get your designer or structural engineer to calculate your timber sizes in two ways so that you can (a) price the lower grade with a larger size, then (b) the higher grade with a smaller size. The design should also take into account the most economical joist spacing. Ideally, do not specify or use a mix of timber grades throughout a floor.

When laying tiles on timber joist floors, use an adhesive laying system on a substrate of weather and boil-proof plywood (WBP) of a minimum thickness of 15 mm, with phenolic glueing and screwed to the floor structure every 300 mm.

Notches and holes in joists

The building regulations have limitations on how much and where traditional joists can be notched or drilled to allow cables and small-diameter pipes through them. If it is expected that excessive numbers or sizes of notches or holes will be required, such as in a floor above or below a room which contains a high ratio of service fixtures and fittings (perhaps a kitchen), it may be necessary to increase the designed joist size accordingly or look for an alternative solution.

Open web joists

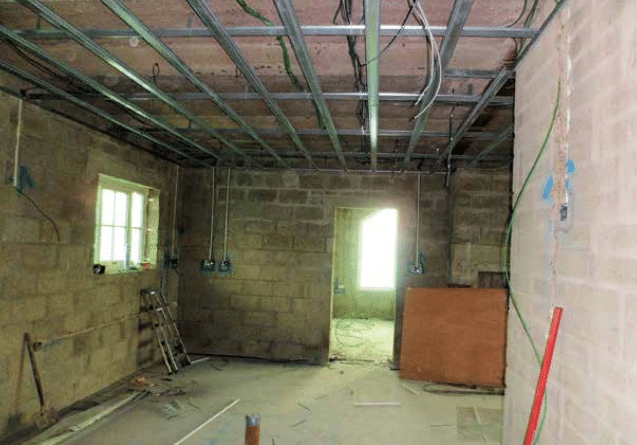

Also known as space joists or open metal web joists, these are sold under a plethora of trade names and offer a modern alternative to the traditional joist. They are typically made using a length of timber top and bottom, with diagonal galvanised steel webs separating the two.

They have certain advantages over traditional joists in that they will span across much greater distances to create larger open plan floor areas underneath and they possess inbuilt spaces which will accommodate cables, ducts and pipes.

These openings avoid the need for notching and drilling normally required to get pipes and cables through joists, thus reducing the possibility of weakened floors, all with the benefits of reduced labour

costs. The main disadvantages are that they may require a longer lead time when ordering and will be more costly than traditional joists.

I-joists

I-joists are another prefabricated system lying somewhere between traditional joists and open web joists. These are so called because they look like a capital letter ‘I’ at the ends, being formed of a run of small section solid timber glued along the top and bottom of a plywood ‘web’. These offer potentially longer spans than traditional joists and have a much smaller solid-to-void ratio which offers an

improved thermal performance when insulated. They should not be stored or used where moisture may be a problem.

Attic roof trusses

Attic roof trusses may be used to create rooms in the roof space. The bottom chord of the trusses perform the job of floor joists and the whole timber roof structure is carried on the external walls. A few structural questions have to be considered, such as the need to joint multiple trusses together, for instance on each side of openings in the roof (e.g. windows and chimneys) or in the floor (e.g. stairs). Fire regulations will also require things like fire-resistant ceilings, floor decking in voids and firestops; in order to reduce the risk of fire spreading between storeys.

Engineered timber

Engineered timber is manufactured by layering timber boards, veneers, fibres, or chips and binding them all together using heat and pressure and/ or special adhesives. It is designed to maximise the natural strength, uniformity and straightness of the timber and comes in a range of different types which may be used as joists, beams or rafters. These types include parallel strand lumber (PSL), laminated strand lumber (LSL), glued laminated timber (Glulam) and laminated veneer lumber (LVL). The first two are available but do not have common standards for production and are not included in British Standards or Eurocodes, so their use could prove difficult in gaining building control approval. It is the last two that we would normally encounter in the UK and Ireland.

Glulam is the shortened name for glued laminated timber and is made by finger-jointing planed timber boards lengthwise and then glueing them together in layers to make long large-sized sections. It is generally chosen for its excellent load-carrying ability and aesthetics and can be made in curved shapes, with concealed connections. This is the type of engineered timber that you will often see as exposed roof beams and support posts in larger open plan buildings.

LVL manufacture begins with debarking logs, conditioning them in hot water and then slicing the timber into the thin strips or veneers of no more than 3mm thick. The strips are scanned for defects, dried to a moisture content of between 8 to 10 per cent and oriented in the same direction. They are then coated with an adhesive and heated under pressure and cut to the required sizes.

Although each comes in different strength grades, LVL is typically stronger and cheaper than Glulam but doesn’t look as good, so tends to be used in structural situations where appearance is not such a critical factor.

Timber quality and strength

The two most commonly available softwood grades for general use structural timber are C16 and C24, with TR26 being supplied for trussed rafters.

Hardwoods are given D numbers from D18 to D70. These are all strength grades, but to be technically correct, the grading of species such as Spruce and Larch in the UK and Ireland tends to be governed by

stiffness.

All structural timber should be properly marked with a stamp that shows the supplier’s licence number, the machine number, timber species, chain of custody (CoC) number, the standard number (i.e. BS or

EN) the strength grade and the certification body (e.g. BM Trada) and its quality mark (i.e. Q mark).

Other logos on the stamp should include the supplier’s company name or logo and KD to show that it has been kiln dried.

All timber used in construction projects should be sustainably sourced from forests where more timber is grown than is harvested and should all carry a PEFC logo (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification) or an FSC logo (Forest Stewardship Council Certification).

Timber marked DRY is graded at a maximum moisture content of 20 per cent and should be transported, stored and installed in the building in a manner that does not allow this moisture content to be exceeded.

Although a moisture content of 20 per cent or less is permissible for internal use, timber joists used in

intermediate floors for instance, can dry to around 12 per cent moisture content, so expect progressive shrinkage as the timber dries over time.

Sometimes a lack of knowledge sees timber being cut lengthwise from a specific grade such as C24 to provide two or more smaller section sizes. This procedure will not necessarily result in two or more smaller section sizes of C24.

More alarmingly, we occasionally hear of ungraded timber being unofficially stamped to make up a shortfall in available graded timber. This practice is harder to control, but you should be aware that if it looks like it is poor quality, then it probably is.

Warning indicators would include wet timber, a higher than expected number of irregularities such as holes, notches, knots, wane (an uneven edge caused by a residue of bark), a discontinuous or sloping grain and maybe splits or shakes (the splitting of the wood fibres along the grain).

Given the cost of timber nowadays and the safety implications of using an inferior quality, it is imperative that not only is all timber obtained from a reputable supplier, but that you check it before it is used.

If you don’t know enough about grade marking, a reliable reference source such as the Timber Development UK (TDUK) website is a good place to start learning. Easier still, if you have employed your designer to act as the independent certifier for the project, he or she can check it for you.