In this article we cover:

- What is passive house and why it pays to invest

- Cost of building passive vs building regulations compliant

- Performance gap

- Issues with heat pumps underperforming

- Quality control on site

I started my journey with the Passive House standard, as defined by the Passive House Institute in Germany, eight years ago in 2015. In this time, the most common question I’ve been asked by self-builders is: why not just build a nearly passive house? My answer is: why would you go near passive when you can achieve the higher standard with just a little bit more money and effort, and reap way more benefits.

If you think about it, you can reduce your heat load by a third if you go from nearly zero energy building (nZEB), which is the current regs compliant standard in ROI, to full passive house.

In NI, despite a recent improvement and changes expected for 2024, the regulations are significantly behind the rest of Europe, and the rest of the UK, with respect to thermal performance. So the savings you could make there are even higher.

What is a passive house?

Passivhaus, literally passive house in English, refers to buildings created to rigorous energy efficient design standards so that they maintain an almost constant temperature.

Passive House buildings are so well built, insulated and ventilated that they retain heat from the sun and the activities of their occupants, requiring very little additional heating or cooling.

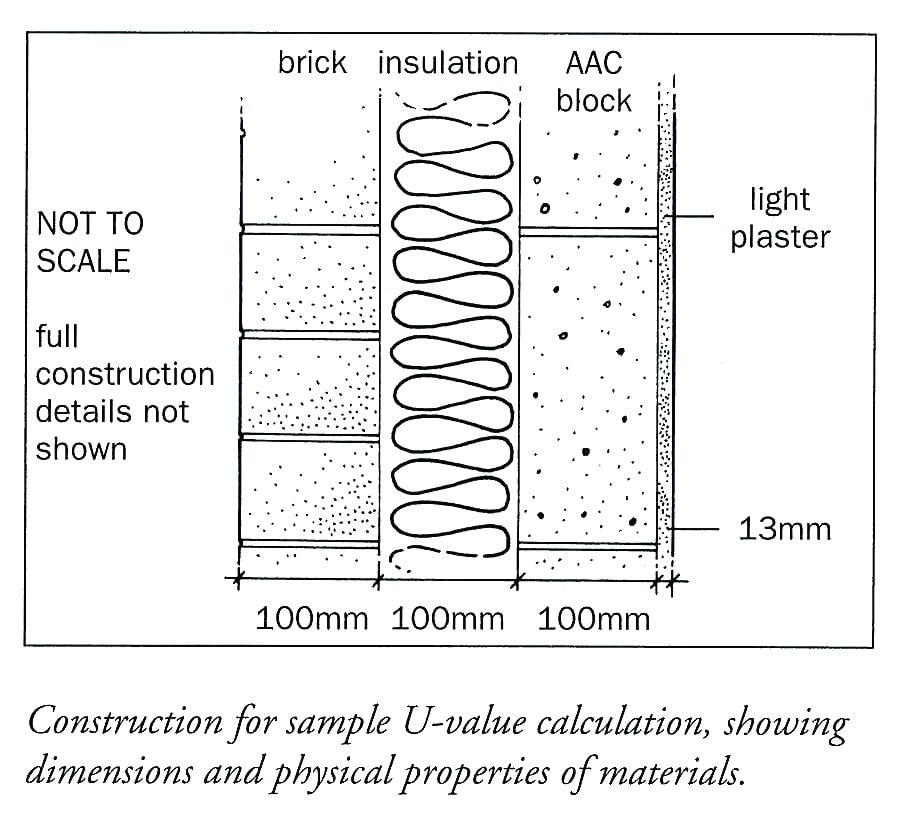

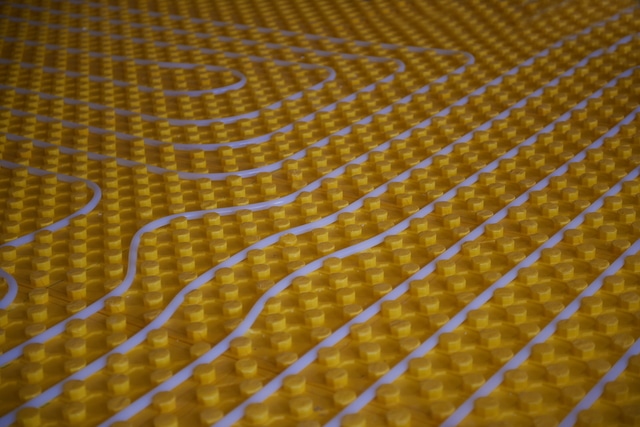

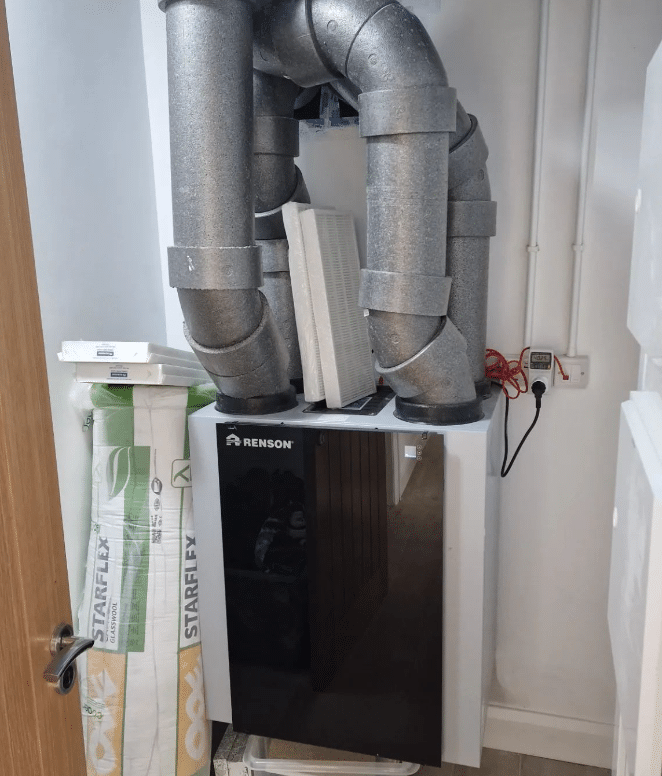

The actual construction methods of passive house buildings are not prescribed and will vary but they will all have the same five principles, including: super insulation, mitigation of thermal bridging, triple glazing with insulated frames, airtightness and finally mechanical heat recovery ventilation.

In the context of other factors which result in higher build costs (high-quality, high-performance building products, design form, ground conditions etc), this becomes a minor uplift for a far superior product in terms of running costs, carbon emissions, and additional co-benefits such as comfort and health.

Performance gap

Many studies show a performance gap between energy ratings and actual energy use. Meaning your house may look really good on paper, with a top of the class energy rating in the A band, but in reality it is performing well below that.

A recent study by Irish academic Shane Colclough found that any A2 homes were in effect, based on monitoring data, a B1 and in one case a C1.

Yes, the building regulations in I Ireland are progressive in that they are nZEB. Thermally, the metrics are almost at passive house standard numbers. But metrics mean nothing if they are not put into practice.

The primary issue here is quality control, of both design and construction. At design stage, the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) can be used as a design tool for use from the very beginning, at the concept stage where aspects like form factor, surface area to volume ratio, and how many windows to put in, are all taken into account.

During the construction phase, the Passive House quality assurance framework ensures there’s an independent third party in the form of the certifier who will require evidence of good execution on site.

There are other ways to keep on top of quality control for the build, but the point is that you need to pay close attention to both design and construction to minimise the likelihood of performance gaps

Heat pumps underperforming

I hear of people in the self-build community quoting incredibly high energy costs for operating their heat pumps. There may be other reasons, including what the settings are on the heat pump, but one reason could be that the building envelope of the home is not as energy efficient as it claims to be, or was designed to be.

A heat pump works well running on low temperatures which means the house needs to be able to retain heat for it to work efficiently. You need a well insulated and airtight envelope for it to heat your home at a low cost.

A good analogy is to think of the other heat pump we all have in our homes… our fridge. It’s made the same way as your heat pump only it’s in reverse thus providing cooling rather than heating.

Now if we look at the envelope of a fridge; it is a continuously insulated box (no thermal bridging) with an airtight seal at the door. We all know that we would not leave the fridge door open. If we did our food would go sour but more relevant here is that the little heat pump at the back of the fridge would go mad trying to refrigerate the entire kitchen.

Doesn’t passive house cost more to build?

Today, the cost of building to a Passive House standard has come down a lot due to the methodology becoming more widely adopted and passive house products more widely available.

Analysis shows that the extra costs associated with building to the Passive House standard in the UK has reduced over the years and, back in 2018, best practice costs were around 8 per cent higher than comparable non-Passive House projects.

However, removing the costs associated with quality assurance (to eliminate the performance gap, this should be done regardless) and considering further development of skills, expertise, and supply chain maturity, indicates that extra costs could come down to around 4 per cent or less.

In ROI it’s pretty much cost neutral, albeit a bit more expensive, to go passive house considering the small differential in the building regulation requirements. This is likely to reduce to nominal levels if adopted at scale.

Quality control

It’s important to point out that passive house certification costs are comparable to those of any other build, as self-builders need to pay for someone to oversee the build. In my experience, even a motivated client needs an external assessor to drive a continuous focus on thermal quality.

Without a certifier, initial enthusiasm to make sure the structure is kept airtight tends to fade as the project progresses, and often, thermal continuity and overall quality also suffer as time wears on. A certifier brings focus, which means that standards are less likely to slip.

Certification looks like an extra cost for a plaque on the wall, but…. It is an essential part of challenging our business as usual mentality. It ensures the golden thread of intent and quality exist throughout the process. Certification costs are marginal compared to the assured benefits.

In both jurisdictions there is good reason for pursuing the passive house standard. In ROI quality control is done through self certification rather than a building control body. (Even if you have an Assigned Certifier, at the end of the day you’re the one directly paying for their services.)

And in NI the regulations are a long way off achieving high thermal quality. Which means it will cost more to go passive house, making it less attractive. Instead of insulating and ventilating their homes to a high standard, many instead opt for adding photovoltaic panels to boost the energy rating.

The bottom line is, there are way too many examples of buildings that do not perform. We are all now at the junction of a climate imperative, an energy crisis coupled with a cost of living crisis. It’s time to build homes that keep us warm without it costing a fortune. In my view, the Passive House standard is a surefire way to get there.