Most self-builders who choose to hire a main contractor to oversee all the work on their self-build project will go to tender, unless they are sure of who they will be hiring.

A standard tender process should be well structured and will generally be made up of a number of stages. These include the tender documentation, selecting the list of tenderers (the builders you are going to ask to submit a price), carrying out the tender

analysis, post tender negotiation and lastly, final selection and contractor appointment.

Rules of the game

Tendering is in many ways a game we play in the world of construction, with a view to seek out the most economical cost of getting building work done.

Even though some may take issue with this interpretation, a game is very much what is at play when you go seek prices in the marketplace. The game being played by any contractor or supplier, is of course to get sitting or communicating directly with you in

order to win the works package.

With any game, it is vital that those engaging in the process understand the rules, as otherwise what chance have you got of surviving to the end without, in some way, losing out.

The amount of loss will most likely be determined by either pure luck or the goodwill of the many genuine and honest contractors and suppliers in the marketplace.

Tendering your self-build, if managed effectively, can be an enjoyable, interesting and at times rewarding process where you will really get to the heart of the components and pieces of the puzzle that will make up the various elements of your house.

To a large degree, effectively managing the process simply means having a control

system in place to stay in charge throughout. A loss of control in tendering will most likely result in the addition of numerous variations to costs and specifications at a later stage in the project, at a time when you have lost the power of seeking costs on a

competitive basis.

The process to be followed will be exactly the same for a single trade package (less common on self-builds) as it will be for a single overall main contractor tender.

Tender documentation

The key to a successful tender is the amount and detail of documentation that you can supply. These are referred to as the tender, or the tender documents.

The first thing that needs to be reviewed and decided is the basis on which the contract between the parties will eventually be made. The selection of the contract can in many ways dictate the level and type of tender documentation that is required.

In NI and ROI the most common two methods of contract are known as (1) the drawings and specification contract and (2) the re-measurable contract.

For a drawings and specification contract, the contract sum will be deemed to include all of the items noted or reasonably implied by the drawings and specification. The onus will therefore be on the tendering contractor to ensure that the price submitted fully includes all items necessary for the subject package (be that a single trade or the full main contract package).

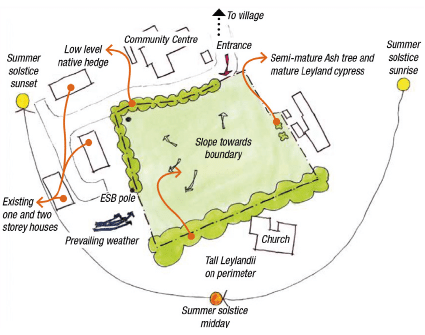

For many therefore, this tender process involves nothing more than issuing drawings to contractors for pricing. This can work perfectly well from a tendering perspective when the drawings are fully detailed, the items required are fully specified and there is no interpretation possible in respect to what is required.

The difficulty arises when, due to a lack of clarity, two different contractors can see an item in different ways leading to two different interpretations and subsequent prices. This is akin to the old saying of comparing apples with oranges.

A further issue can arise from the fact that contractors revert with tender prices in different ways. One contractor may simply supply a single cost to complete all of the work noted on the drawings (I will build your house for x). Another contractor may provide breakdowns for the cost of various high level trades (electrics, plumbing, walls, etc.) and another contractor may give a greater level of detail. How can you therefore compare these prices?

Tendering should always be very much geared towards having a clear and concise system where everyone prices the same way (comparing apples with apples) so the outcome can be unambiguous and everyone is working on a level playing field.

In order to achieve this outcome, it is beneficial to have a pricing schedule (or bill of quantities) developed to be issued to the contractors along with the drawings and specification.

A pricing schedule can be a simple list of the various tasks required for the project (foundation, external wall, and so forth) against which tendering contractors insert a price, or it can take the shape of a fully detailed bill of quantities where every single item required is individually measured (concrete to foundation, mesh to foundation, etc.) and listed for the contractor to insert a price.

In a drawings and specification contract, the responsibility for accuracy of any quantities will be a contractor risk item and something they need to check and clarify. If a bill of quantities is supplied by the client in a tender, it is still down to the contractor to check the quantities to ensure they are correct.

The benefit of a pricing schedule is that it allows for comparison of prices across a number of headings or items across all of the contractors which will highlight price anomalies that can subsequently be discussed in later stages with contractors.

Clearly the more detailed bill of quantities will provide an even greater level of comparison across a multitude of more prices. The bill of quantities without doubt will provide the most accurate level of comparison where apples really are compared with apples.

On a re-measurable contract, the bill of quantities will be a compulsory requirement for the tender, as the bill itself (as opposed to the drawings and specification) will form the basis of the contract between the parties and each item when completed will be re-measured based on the quantities used onsite and the rate that was tendered for that item will be used to calculate the end value.

The bill of quantities therefore is used at tender stage to estimate as near as possible to the quantities envisaged, the contractors insert prices against each item at tender stage, and they remeasure and claim for the actual quantities installed following construction.

This level of data will also provide a clear basis for the valuing of variations at a later stage in the project when the prices of individual items will be available at the outset.

To put the issue of clarity in pricing in a simple way, the table on the previous page is an example of how one section can be dealt with across the different tendering options.

What is clear from the table is that providing more than the drawings and specification alone will provide the client with more data to analyse the prices of contractors, to ensure that nothing is missing, and to identify when a contractor has overpriced or more importantly, under priced an item which in many instances could become an issue on site at a later stage.

Selecting tenderers

So you have your documents ready to go, how do you pick the list of who to send the tenders to? There is no real correct answer to this question.

Many people compose their tender lists directly from the recommendation of others. This could be from their designer (or wider design team) and their previous experiences of that contractor, others come from the recommendation of friends or family who had previous works completed. Others will come from magazines, publications, social media or similar advertisements that contractors engage with. A common route to the tender list is from the names of contractors on site hoardings in the locality or from simply being the local builder that everyone uses.

Whatever way you select your contractors or tradesmen, ensure they have references that you can check (never be afraid to knock on the door of a reference by yourself and chat to their previous clients about their experience), ensure they are fully insured and that they are fully tax compliant.

It is standard practice to send your tender to at least five contractors in the local marketplace. A reason for this is to ensure you get a competitive result.

Tender analysis

It is generally the case that for an entire new build project with a single contractor, a period of two to three weeks will be required for the tender. Individual trade tenders will obviously take and need less time to tender but no matter what time you give, you should ensure that all those tendering get an equal time and that the cut off point for receipt of tenders is clear.

On passing of the cut-off point, the tenders should be analysed on a like with like basis to ensure that each contractor is compared fairly and equally. This ensures that all tenders are compared on an apples with apples basis and ensures that any issues of excluded items, over pricing or under pricing are identified and discussed with the relevant contractor. This also ensures that the specification included for the item in the tender is that which is priced by each contractor.

Obviously the level of comparison is directly dependant on the documents issued with the tender. The more detailed the tender pricing document, the more detailed the analysis. A bill of quantities will allow for analysis across the likes of the cost of a double socket, a pricing schedule will allow analysis across the likes of power as a whole, whereas a drawings and specification may result in an analysis of just the electrics value as a whole or less.

When the tender analysis is completed, this should provide a view as to where each contractor sits and it should develop the agenda for discussion with each contractor. It is generally the case that following analysis, the list of contractors is reduced to two or at most three contractors.

Post tender negotiation and contractor selection

It is then common to meet with the reduced list of one, two or at most three contractors to review their tender, seek clarity in respect to any issues the tender analysis identified, to seek comment from the contractors in respect to any issues they foresee on the project or in the design, to discuss the view on proposed duration for the project (which can often help in the selection process) and to simply meet the person to see if you can work with them.

Knowing that this will be a relatively long-term relationship, for at least a number of months, it is very important that you can see yourself working with the selected contractor. Personality clashes can easily lead to conflicts on site.

Once these meetings take place, and contractors have updated their best and final positions based on any issues raised at the meetings, a contractor is declared as the preferred contractor.

The decision can be based solely on price, it can be based on quality of previous works, it can be based on the duration the contractor is proposing to complete the works or it can be a mixture of these items. It is not necessarily just based on the cheapest price.

Then the contract is drafted and signed before the parties proceed in their partnership to complete the works, starting with notification to building control.