In this article we cover:

- Basic building regulations

- Reaching a balance between how much insulation to put in and an energy efficient home

- Energy strategies for the floor, walls and roofs

- General guidelines for different insulation products

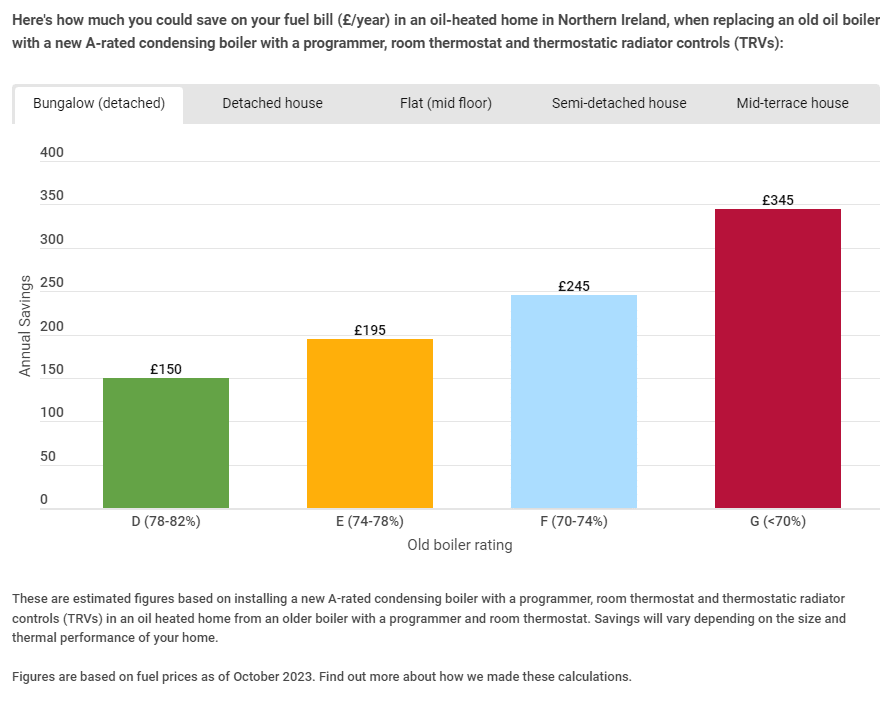

Your energy strategy in a new build will at the minimum, have to meet the building regulations. The regulations in ROI are stricter than in NI.

Basic regs

The building regulations require that you build to minimum U-values, although the calculation method is in fact more sophisticated than this as it relies on energy and carbon modelling.

But there are minimums you can’t exceed, as outlined in Part L (ROI) and Technical Booklet F1 (NI). Remember, the lower the U-value the better the element is at preventing heat from escaping.

New builds in ROI must be NZEB, which is reflected in the low/good U-values you must achieve. As for airtightness, there are minimums too. The minimum as specified in the Building Regulations in ROI is 5, and anything below 3 de facto requires mechanised ventilation (see previous edition for our Systems Guide).

In NI, currently you can input a default value of 10. Best in class is the passive house standard of 0.6 ACH which is approximately less than 1cum/h.sqm.

It’s difficult to know exactly what airtightness measurement you will get at the end of the build until you do a test, but most building designers will ensure the envelope is kept airtight, most commonly with membranes.

Energy strategies for the walls

When it comes to choosing an insulation and airtightness strategy, there are two options. Integrate the insulation and airtightness within the structure, or add it on later.

Modular building methods such as prefabricated concrete modules or timber equivalents known as SIPS or Structural Insulated Panel Systems, apply the insulation in the factory. Junctions are then dealt with on site, after each of the panels have been slotted into place.

SIPS are formed like a sandwich of two boards, usually OSB (Oriented Strand Board) or plywood with a ‘filling’ of insulation, normally EPS, XPS or PUR. All the openings for windows, doors and services can be cut in the factory and the panels delivered to site with the frame of the house erected in a matter of days.

Using a similar idea, only inside out in a sense, is Insulating Concrete Formwork whereby a shuttering of expanded polystyrene is erected and concrete poured into the ‘mould’.

The double layer of polystyrene results in U-values ranging between 0.31W/sqmK (EPS) and 0.26W/sqmK (XPS) which can be increased with the addition of insulated plasterboard on the internal leaf. As a monolithic structure, ICF is both inherently insulated and airtight once the pour is complete.

Cavity wall construction and conventional timber frame require that you layer on your insulation and airtight membranes after installation.

Therefore the first step to devising an insulation and airtightness strategy is to choose your building method, and then carry out an energy assessment to determine the optimal levels of insulation and airtightness products to install.

Another option for inherent airtightness is cob construction. This is a method that has been around as long as humans have been creating habitats and settlements and is made from the very materials most ready to hand – earth, water, straw, lime, etc. – essentially the African mud hut or the American adobe house.

It is extremely robust, reasonably energy efficient in operation due to its thickness (thermal mass) and the thermal properties of earth. It’s an excellent regulator of moisture (when used with a lime plaster) as well as being airtight. It can also be formed into a wide variety of forms including, it should be said, entirely conventional orthogonal ones! It is also extremely fire resistant and eminently recyclable. Downsides include labour intensiveness and long construction time (including up to a year to dry out), plus it not being considered standard construction so possibly harder to insure and get signed off on by your engineer or approved by building control.

Energy strategies for the floor

Standard floor construction consists of foundations made up of concrete and steel, with insulation and screed on top. The insulation is often PIR board but can also be the more efficient phenolic board, or the more cost effective but less efficient EPS boards if you can allow for enough depth.

At the perimeter a thin strip, often 25mm, of PIR insulation board should be added added to prevent thermal bridging (most of the heat from a solid floor is lost at the edge of the slab). In addition it is common to have aerated concrete blocks which are more thermally efficient than standard blocks.

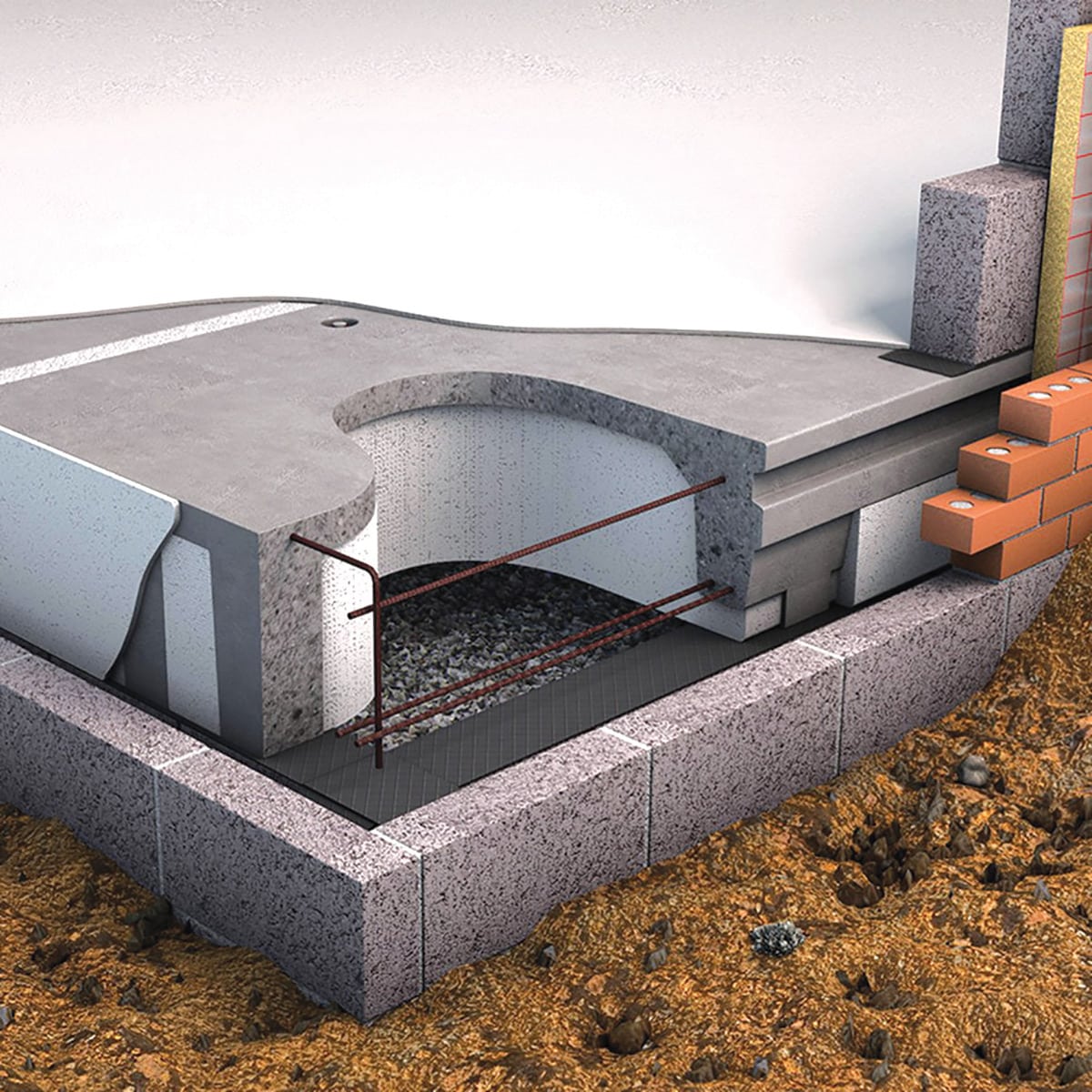

As with the wall, you could choose to integrate the insulation with the structural component. Insulated foundations are proprietary systems, often consisting of EPS insulation, that pour the concrete into EPS moulds, similar to the ICF walls.

In the case of a storey and a half, or a two storey house, you may choose a precast concrete floor, which will be craned into place. Where the slab meets your wall will cause a thermal bridge if not insulated, as concrete is not a natural insulator. Preinsulated slabs are now quite common to get around having to insulate this junction on site.

Energy strategies for the roofs

There are two ways to insulate roofs. A warm roof insulates at the rafters, keeping the attic warm. A cold roof construction insulates at the attic floor, making the roof cold in winter.

Warm roof construction is fairly standard, even if you only use the attic for storage space, and in that case, a common roof build up will include mineral wool between the rafters and PIR or phenolic board underneath them. There are many variations and it will boil down to the U-value you are aiming to achieve. You can also include an insulation sarking layer on the outside which will remove any possibility of interstitial condensation and avoid the need to ventilate the topside of the rafters.

Airtightness membranes are usually added within the build up, which is most commonly finished off internally with plasterboard and skim.

Similar in construction is the cold roof method, with insulation between joists and often above, usually finished with chipboard or similar, depending on whether it will be used as living space or for storage. Trickier in cold roof situations is if there are any services present, such as a cold water tank or ventilation unit, which may need insulating if not already.

More expensive are preinsulated structures. ICF roofs are possible but not common for this reason, while concrete modular roofs are also possible but have restrictions on the pitch, for example. Preinsulated roof board ‘sandwiches’ are available too but don’t benefit from the overlap of the more traditional method of two layers of insulation.

Other considerations

Some insulation products are more vapour permeable than others, which can be a key consideration if you are building with timber frame, for example, although non permeable alternatives can work equally well if the airtightness and vapour control strategy are well devised.

If you have a concrete block cavity wall and decide to insulate all or part of the cavity, you will often then be presented with the option of adding further insulation internally. This is commonly done by adding insulated plasterboard and makes your home better insulated, bettering your U-value. The downside includes losing wall space (mostly an issue for renovations if the room is already small and a lot of internal insulation needs to be added), but also losing the benefit of thermal mass, i.e. concrete and plaster’s inherent ability to store heat and slowly release it when temperatures start to drop.

In the case of a concrete or stone house, external insulation is often the most expensive way to go because of the application and the need to use specialist renders. However, in the case of timber frame, external insulation tends to be standard.

You may also consider the materials’ carbon footprint, as in how much energy it took to produce, whether it is made from recycled materials, and also whether the materials emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) during their lifetime. Some argue that in the case of insulation, as it is all boarded up and hidden from view, VOCs are less an issue than the choice of furnishings as many textiles emit VOCs due to fire retardants.