Irish thatched cottages are regarded as symbols of Ireland in various contexts including the tourism industry and in political ideology. But in its traditional and original form, the Irish cottage must seem alien to those involved in building a home today. Their small size and dark interiors (along with superstition on the design brief) are likely to be offputting concepts for the modern dweller.

But there is much to be taken from them, such as the use of local and sustainable materials and their blending into the landscape. And these are surely methods that today’s builders should prioritise.

Design

Irish cottages are an example of ‘vernacular architecture’, a term which in many ways refers to the first self-builds. Vernacular houses are what the common people built, without the intervention of formally trained architects. If you look at vernacular architecture around the world you will notice it doesn’t adhere to fashions, rather is a response to climate and materials.

Therefore, such buildings tend to be noted for their quaintness and resistance to trends. Most Irish rural cottages look similar, because people did not attempt to be ‘different’ in the design of their homes. This is reflective of the social status quo at the time; people were religious and saw themselves as part of the ‘herd’ and wanted to fall into step with their peers. Not wanting to be seen to be ‘getting above’ themselves, they naturally built in the style of their community.

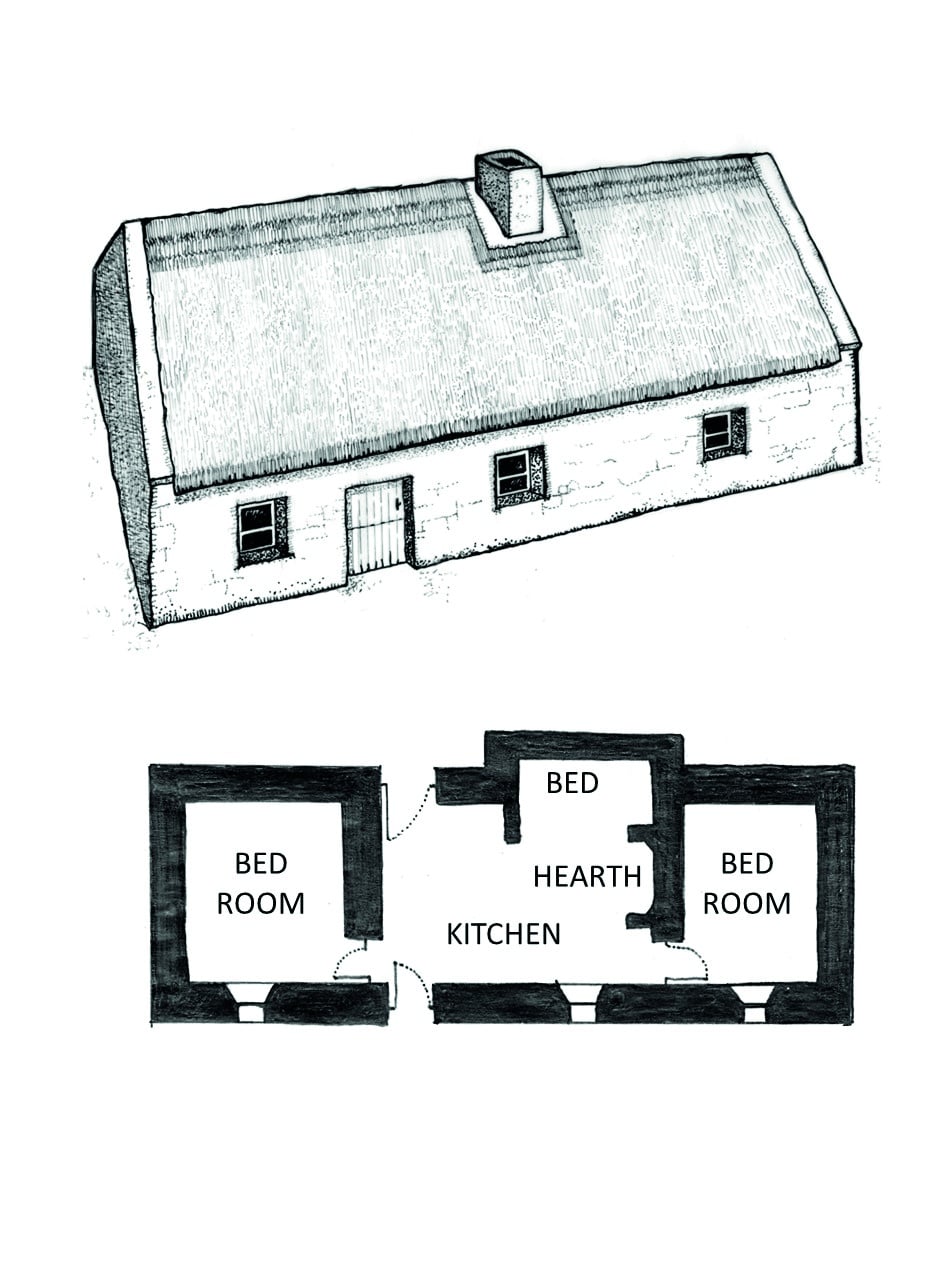

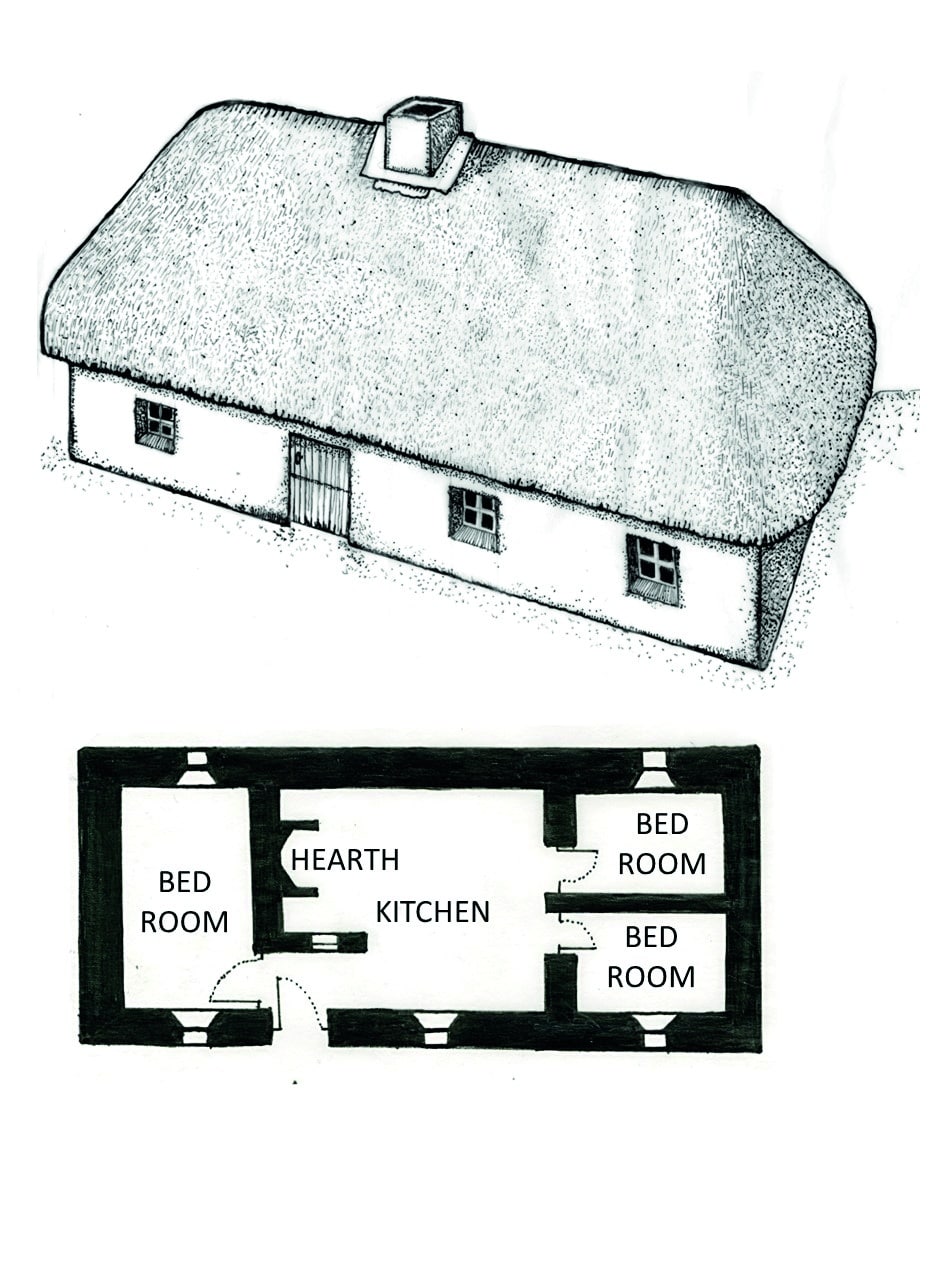

The most common cottage type in Ireland is the single-storey dwelling house, one room deep. These usually have three front sash windows, and a front door offset from the centre. They are linear in plan with no hallways but one room leading to another. Built of stone or clay, whitewashed and thatched, they are characterised by steep pitched roofs to keep out the rain.

The climate of Ireland has had a huge influence on cottage design. The thatched roofs of the wild northwest coast featured raised stone gables and the thatch was additionally secured with rope. The dryer southeast of the country allowed for hipped gables, which were better at keeping rain from the walls. The typical interior would have consisted of either earthen or stone slab floors, with a central kitchen and living room combined, and the two other rooms of the house, the bedrooms, on either side. The small windows would have made for a dark interior. There was originally no indoor plumbing or electricity. In the main room the central feature was a large open fire, providing heat and a cooking area. The fire would also be used as a light source during the long dark winter evenings.

Choosing the site

Where contemporary Irish one-off houses command a view of some sort, and are sometimes sited on hillsides to attain just that, traditional Irish cottage dwellers would have balked at such windy, exposed places, preferring sheltered aspects instead. The selection of a site with access to a well and a plot of land to grow potatoes (or keep livestock) was important. In contemporary design, road access is a chief concern for people, in contrast with our rural ancestors who walked to most places via the fields.

The planning process today is important but in the past religious and superstitious beliefs were crucial in the building of cottages. Many Irish people believed that selection of the wrong site might bring ill-fortune, if the planned house was near a fairy fort for example.

Building practices

There were many other superstitions that governed building vernacular houses. Rooms could not be built, as an extension, west of the house. Stones that fell from a builder’s hand while working could not be inserted in a wall. There was also a custom that stone from an old building should not be used in new buildings.

Stones from a sacred site were never used in a building. There was also a widespread custom of burying items under foundations to bring luck including vessels, metal objects (to deter fairies) and even blood and body parts of animals.

The people who built cottages did not have much money and so would have had to avail of locally sourced materials for cost and transport reasons. The result is a pleasing tendency to blend into the surrounding landscape. When a new home was needed a contractor was not hired, instead the community came together to build it. Members of the community would have had certain expertise in building, thatching, joinery, carpentry, or furniture making. In isolated communities, outsiders could not be easily brought in and local knowledge of building and craft had to suffice. Meitheal was commonly practised in rural communities; this is an Irish tradition where a working group from the community (the meitheal) gathers to help in a member’s time of need.

Cottage Traditions

Milking Parlour – The back and front door layout evolved from the tradition of milking the cows in the house, which was thought to bring good luck. This practice continued up until the 1930s but only during the summer months. Another reason for the two-door system was to prevent changeable winds from entering the kitchen in a culture where the door was frequently left open and the fire was always lit. The back door was known as the draughty door (doras cúil), with the front door (doras tosaigh) facing the sheltered position.

Window design – In most cases there were no windows to the rear of the house and the openings that were there were kept small. Heat retention, not window taxes (the infamous levy had little to no impact in Ireland), was the reason why there were so few. Casement hinged windows were used up until the 1680s when sash windows began to spread throughout the country. The one-over-one configuration became prevalent by the midnineteenth century.

Housewarming – When the house was complete it was not unusual to have an animal occupy it to ‘test’ it for a number of weeks; if the animal died it was considered a bad omen and the house was left unoccupied. For the housewarming party the house was adorned with holy icons and the first fire in the hearth was started with lit fuel brought directly from the dweller’s parents’ home. Dancing during the party helped flatten the earthen floors.

Marion McGarry’s new book, The Irish Cottage: History, Culture and Design is published by Orpen Press orpenpress.com, ISBN 9781786050120, colour throughout with b&w illustrations by the author, €17.99.