2050 is the target year for Net Zero but we can expect the building regulations to change much sooner than that. The proposed changes were published late last year as the Draft (Consultation) Technical Booklet F1.

The consultation suggests that phasing in the new Technical Booklet F1, which establishes minimum requirements for the conservation of fuel and energy in buildings, can be done “early in 2022”.

But that will depend on how quickly the government moves on it. The results from the Technical Booklet F1 (TBF1) public consultation were still under review by the Department of Finance at the time of going to print.

There is usually a six month phase in period when regulations are updated and we may expect the same in this case.

Also, the Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland makes reference to the Future Homes and Future Building standards in England, which suggest that new buildings aim to be “net zero ready” from 2025. The provisional programme in NI proposes similar phases some 18 months later.

So the changes we are expecting in NI this year are an interim step. The second phase will gather evidence for a 2023 uplift, and full implementation of “net zero ready” is meant to happen no later than 2026-27 assuming the proposals for England remain on course.

What will it mean for the building fabric?

The draft document analysed various scenarios but favoured the most ambitious one, and those assumptions are the ones outlined in this article.

The major uplift in the regulations comes from implementing the definition of a Nearly Zero Energy Building (NZEB). Technically, that means making the carbon dioxide Dwelling Emission Rate (DER) at least 40 per cent less than the target value (TER), whereas previously the requirement was for DER to not exceed TER.

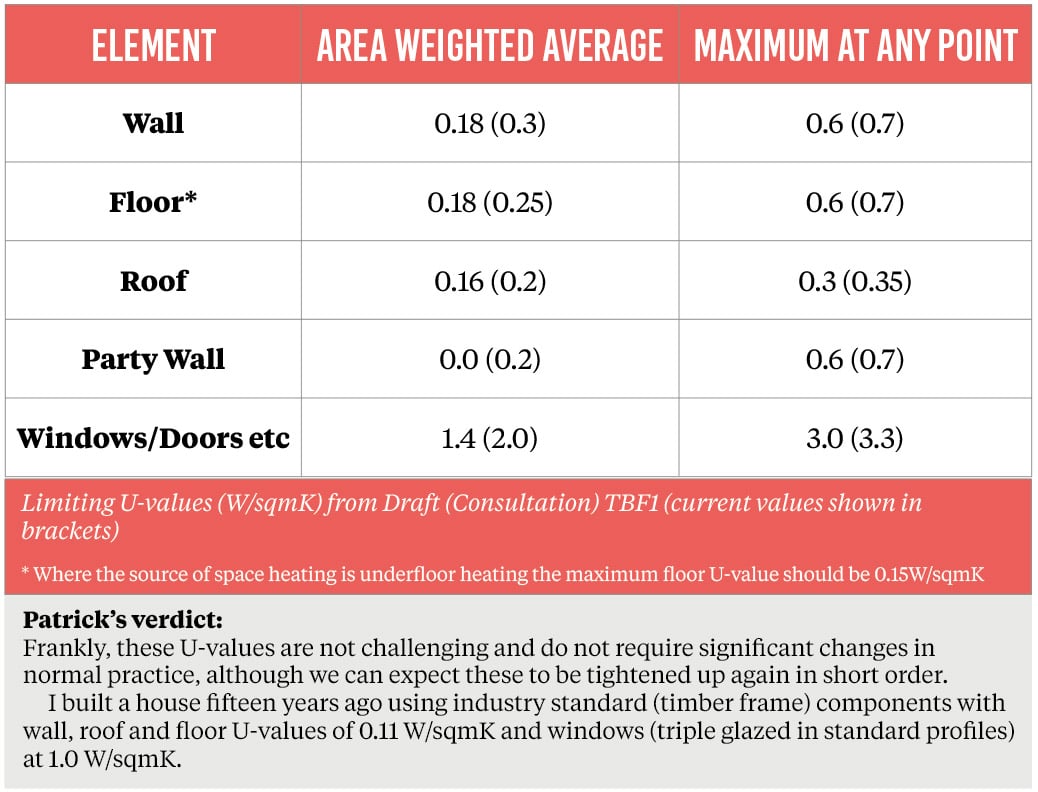

The draft TBF1 gives an indication of what that means for the energy efficiency of the floor, walls and roof with a table of the maximum U-values they are considering. The lower the U-value, the more energy efficient that part of the building is at retaining heat (see below).

What does it mean for heating systems?

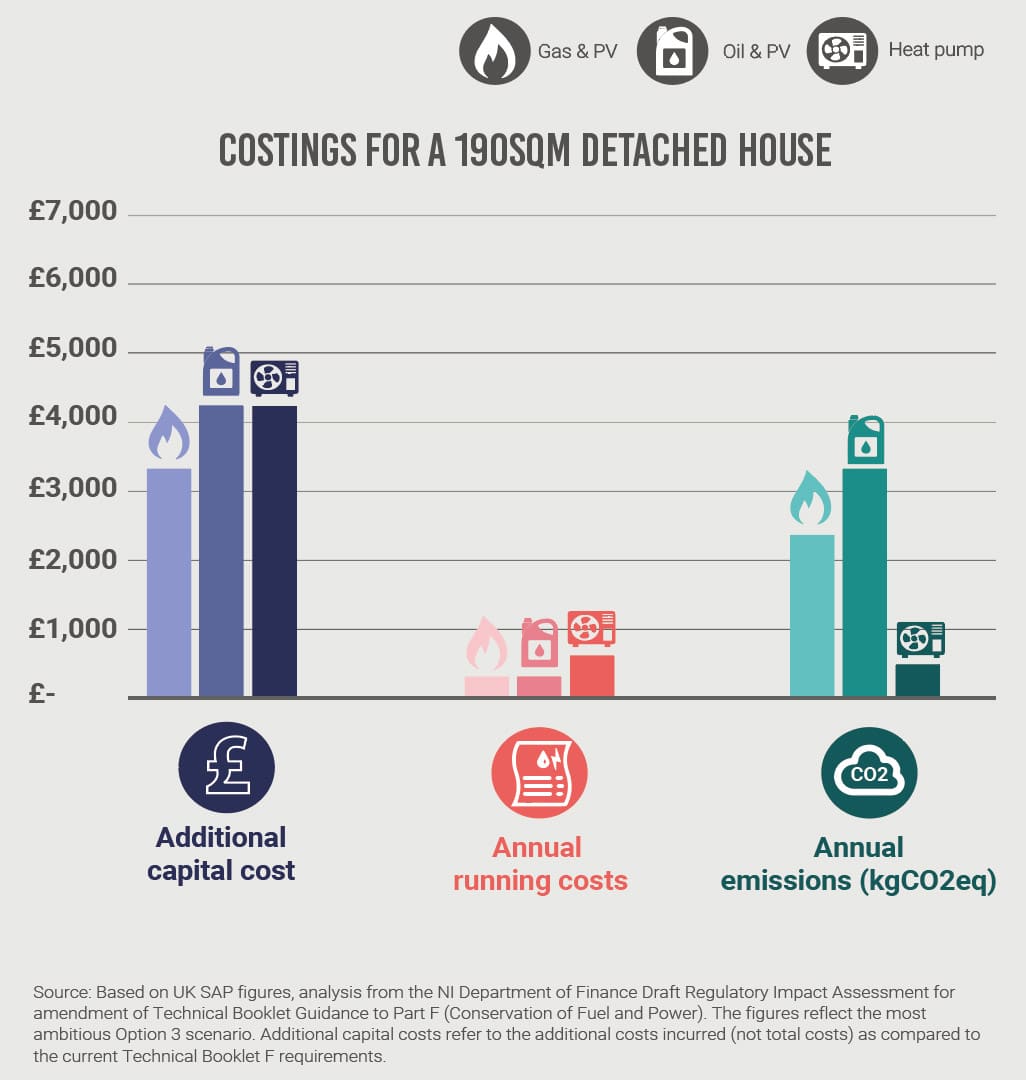

The Draft Regulatory Impact Assessment continues to allow for fossil fuels, but you will need to complement them with solar panels that generate electricity, known as photovoltaics or PV. The three scenarios the draft document analyses for compliance are: gas boiler + PV, oil boiler + PV, and a heat pump.

What are the changes for windows?

There is no real change to the current methodology – the difference now is that you will need to buy better performing windows. The figure of 1.4 W/sqmK for glazing still allows double glazing, albeit the best performing available.

You will continue to have to limit the amount of external doors and glazed openings to no more than 25 per cent of the floor area of the dwelling. This still allows a higher glazing ratio than found in most dwellings, and you can go even higher if you use the calculated trade-off approach which in practice means that if you want more glazing, you’ll need a better performing building fabric (more insulation). Again, no change to current methodology.

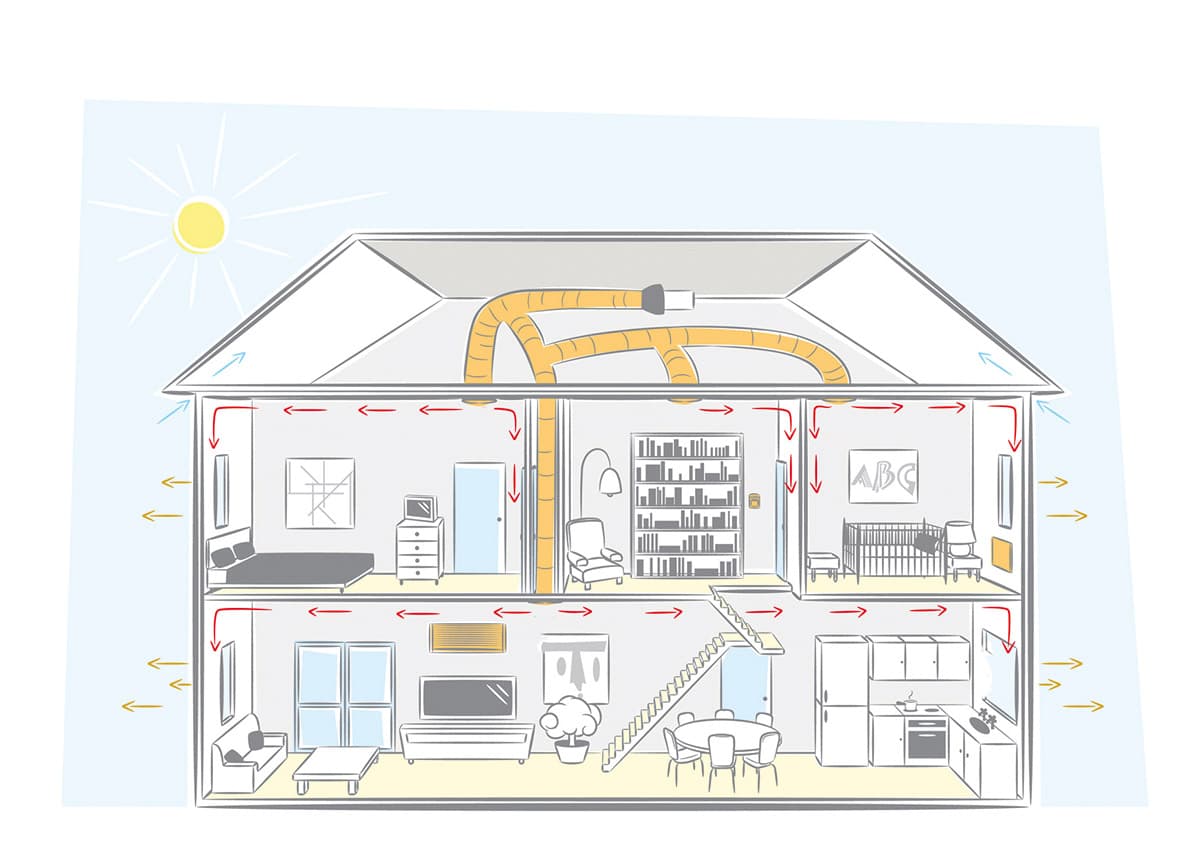

What about airtightness and ventilation systems?

Air permeability measures how airtight the house is, i.e. how much air escapes in areas you don’t want it to. The draft document does not impose any new requirements, the maximum permissible value is still 10 m3/(h.sqm), but it states that “it is expected that dwellings will normally have an assessed air permeability of 5m3/(h.sqm) at 50Pa or less”. The implication being that if you do worse than that you will need to make up the difference elsewhere.

The document adds that where you expect to achieve an air permeability of less than 3m3/(h.sqm) at 50Pa, you would need to consider alternatives to natural ventilation such as a continuous mechanical extract ventilation system. Or you need to “seek specialist advice in order to ensure adequate indoor air quality”.

This is not ground breaking – an air permeability of less than 2m3/(h.sqm) at 50Pa is well within the grasp of self-builders and is needed to get good efficiency from a mechanical ventilation system.

The draft document does, however, implicitly require that you measure your thermal bridging value, (Y-value), which refers to specific areas of the building where heat can escape due to an interruption in the insulation and airtightness layers. Thermal bridges can cause condensation and therefore need to be minimised as much as possible.

You could still use a default Y-value (of 0.15W/sqmK) but by doing so your U-value calculations will be knocked back 15 per cent.

Will there be a renewables requirement?

Even though renewables are not going to be mandatory, I would suggest that some degree of renewable or low energy technology is going to be a de facto requirement for new dwellings. That’s because buildings will have to hit demanding carbon and energy targets, measured as an improvement on a notional building (DER versus TER).

Substantially bettering your building’s carbon emissions will not be easily met by building fabric measures (low U-values) and services (ventilation) alone. The draft document in fact expects “a greater use of renewable generation technologies” and recommends engagement “at an early stage with Northern Ireland Electricity Networks (NIE) to confirm that an export connection can be provided”.

Where an export connection cannot be provided, the SAP software (which does the energy calculations to prove compliance with the building regulations) “will assume that the full generation capacity of any renewable generation technology is being used and the reduced performance due to the inability to export will not be taken into account”.

However, it is noted that “future versions of software are being developed which may take into account any performance losses” and “designers should consider options such as… battery storage capacity or other diverter technologies”.

How much will it cost?

These changes will inevitably increase the cost of commissioning and constructing buildings – we have already seen a rise in the cost of building materials and energy costs – which will impact significantly on self-builders.

Additional costs will come from the additional insulation and airtightness measures required to achieve the stated U-values, and from installing a heat pump, or PV panels to complement a fossil fuel boiler. Plus the cost of improving the thermal performance of your windows; for uPVC windows the draft document says reducing the overall U-value by 0.1W/sqmK costs £10 per sqm of openings.

Walls will cost £18/sqm more to achieve a U-value of 0.18W/sqmK, as the current average in new builds is 0.21W/sqmK. Floors and roofs will not cost any more than they do now, as the average new builds already exceed the minimum U-values in the new regs.

In a detached house, you can save £1,400 by not installing a gas boiler but a 10kW monoblock air source heat pump for a 190sqm detached house will set you back £5,500 plus £1k for the unvented hot water cylinder.

The draft document says your air source heat pump will on average need to be replaced every 20 years and need to be serviced as often as a gas boiler and at the same cost. In a detached house, if you don’t go with underfloor heating you will need 19 low temperature radiators which each cost £75 more than high temperature rads.

PV panels, meanwhile, are expected to cost £1,100 per installation and £700 per kWp installed for systems below 4kWp, or £970 per kWp installed for larger systems. The draft document estimates you will have to replace your system every 30 years and your inverter every 12 years. With maintenance on the panels £100 every five years.

What are the changes for renovations?

There are no significant changes to existing dwellings in the draft document, apart from the advice to take up renewable technologies. The requirements to improve thermal elements if carrying out work to more than 25 per cent of the building envelope area or more than 50 per cent of an individual element have been in place for quite some time.

Will it make a difference to the environment?

We are gearing up for the end of combustion systems in new buildings and a shift towards electric heat pumps… how times change. It’s not that long ago that electric heating was a dirty word and mains gas was being promoted as the clean, environmentally friendly option!

That aside, buildings account for almost two thirds of carbon emissions in NI – the remainder coming mainly from transport, industrial processes, agriculture and energy supply. So changes in building regulations should help, but they need to target existing buildings too.

And those of us who remember the energy targets set in the 1990s or, more recently, the targets for 2020 will know that time flies. We are now over halfway between 1990 and 2050 and have reduced energy related carbon emissions by only 25 per cent.

There is also an intermediate target of 56 per cent reduction by 2030 – less than nine years away – itself a huge challenge. The 2030 target is comprised of two secondary targets: 25 per cent energy savings from buildings and industry and 70 per cent of electricity consumption from renewables.

We have a long way to go, but the urgency of the climate crisis finally seems to have dawned on politicians which gives a reason to be hopeful.