In this article we cover:

- Preservatives for timber

- Types of chemical treatments

- Use Classes of timber

- How fire resistant is timber?

The ecologically balanced first step approach to timber preservative is that if it doesn’t need it, don’t use it. Nevertheless, treatment of timber allows the use of more perishable timber species and those parts of a tree (sapwood) which are more prone to decay. This allows the forestry industry to minimise waste and maximise its resources and reduce pressure on the more durable and higher value species.

Modern chemical treatments are much more environmentally friendly than in the past, when aggressive toxic chemical mixtures such as copper, chromium and arsenic salts or Chromate Copper Arsenate (CCA), pentachlorophenol (PCP) or creosote were in common use. Nowadays, boron based compounds such as borate oxide (SBX) are well known, non toxic preservatives, but you need to make sure that the particular type used was suitable for your wood. Other safe alternatives to CCA now include ammoniacal copper quartenary (ACQ), copper azole and copper citrate.

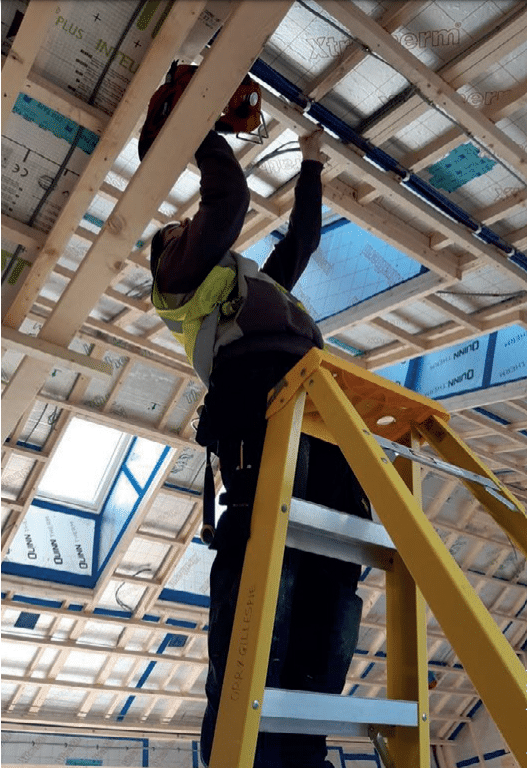

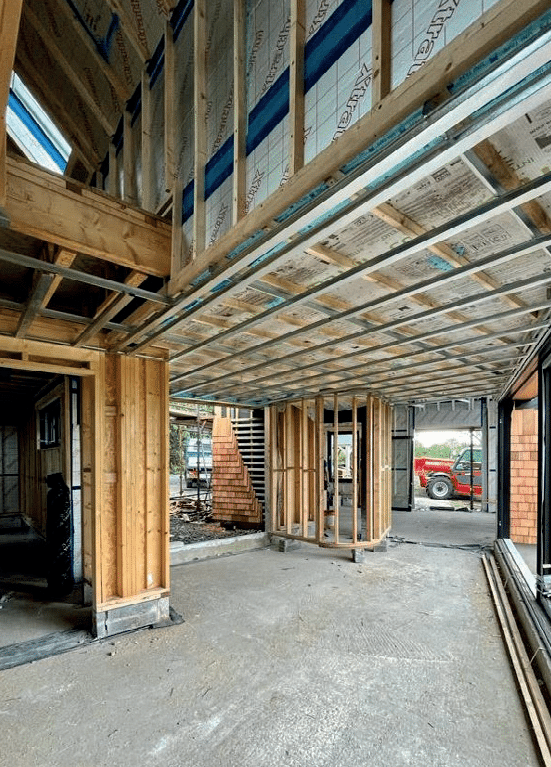

Any wood used in a timber frame dwelling which is likely to come into contact with moisture, wood damaging insects, the weather or external climate conditions, must be treated to combat the likelihood of rot, mould or decay.

Therefore, all timber members in the external walls and in the ventilated and drained cavities of timber frame houses should be treated with suitable preservatives and processes. This should include sole or floor plate timbers of internal walls and any timber in contact with the damp proof courses (DPCs) or damp proof membranes (DPMs). Any timbers which have been cut or trimmed on site must have their ends carefully treated with preservative.

The treatment process is as important as the preservatives used and the best type of process nowadays uses a system of impregnating the timber under a combination of vacuum and pressure, in a large treatment vessel.

Correctly referred to as Vacuum Pressure Impregnation (VPI) although it can be known by various names, the process involves placing a stack of timber in the tank, pumping all the air out, introducing the preservative under vacuum conditions and then applying hydraulic pressure to force the preservative into the timber cells which had been evacuated of air under the vacuum process.

There can be much confusion around the names of the treatment processes, where different names often mean different things to different people, so look at exactly what type of process the timber producer is using and whether it meets the specifications of the timber that you need.

On site, know your products. I once found a joiner treating the cut ends of solid timber with a liquid from a container of a well-know brand of timber preservative that turned out to be heating oil.

For dry timber products, at the time of erection, the moisture content of solid timber members should not exceed 18 per cent and it should not exceed 12 per cent in wood based panels for internal use.

Use Classes of timber

The designer who specifies timber and its treatment for specific uses must have a working knowledge of the timber Use Classes according to EC5, the preservatives suitable for these and the treatment process required to apply them to the timber.

Use Class 1 includes internal, permanently dry wood such as floor boards and other internal joinery. This need only be treated against insect attack.

Use Class 2 includes internal timber with occasional risk of wetting, such as tiling battens, frame timbers in timber frame houses, timber in pitched roofs with high condensation risk, timbers in flat roofs, ground floor joists, sole plates on DPCs or DPMs and timber joists in upper floors built into external walls. These all need to be treated against both insect and fungal attack.

Use Class 3 covers external timber above ground which is exposed to frequent wetting and is split into two subclasses, 3C for coated timber and 3U for uncoated timber. 3C timbers would normally include external joinery such as soffits, fascias and barge boards, cladding, valley gutter timbers and external load bearing timbers. 3U timbers would include fence rails and boards not in contact with soil or decking timbers not in contact with the ground. All Class 3 timber needs to be treated against fungal growth.

Use Class 4 covers wood in contact with ground or fresh water, or permanently exposed to wetting and/or providing exterior structural support. In a domestic environment, such timber would include the likes of fence and decking posts, ground level joists, substructures and gravel boards. All Class 3 and 4 timber needs to be treated against fungal growth and insect attack.

Use Class 5 covers timber in a marine environment which is permanently exposed to wetting by salt water and needs to be treated against marine borers and fungal decay.

Low Pressure VPI is typically used for timbers which have been specified for Use Classes 1 to 3C, where the water based treatment provides an envelope of protection around the timber. High Pressure VPI provides higher levels of protection for Use Classes 3U and 4 timber.

What about fire resistance?

Thirty to sixty minute fire resistance is what’s required for most buildings. With timber frame this is achieved with a combination of internal lining material, usually plasterboard as gypsum is fire resistant, the structure itself (under certain fire conditions, mass timber tends to char which provides a degree of fire resistance), insulation, and fire stops within voids and cavities adjacent to the timber frame construction.

The building regulations therefore cover not only the fire resistance of structural components, but also include provisions to restrict the spread of flame over the internal wall and ceiling linings and, in some locations, to limit the contribution they will make to the growth of the fire. Fire resistance and spread of flame restriction for external walls and roofs are also included in the regulations.